Lewis Hine

Lewis Hine: The Camera as a Tool for Social Justice

Discover the pioneering work of Lewis Hine, the sociologist-photographer whose camera became a powerful weapon against child labor and a catalyst for social reform in early 20th century America.

Featured Works

Lunch atop a Skyscraper

Construction workers sit on a New York City skyscraper girder in 1932. The building today is known as Rockefeller Plaza.

Icarus atop the Empire State Building

A construction worker suspended high above Manhattan during the building of the Empire State Building, symbolizing modern heroism and human achievement.

Workers on Girder, Empire State Building

Steelworkers during the construction of the Empire State Building, demonstrating the courage and skill of modern industrial workers.

Little Fannie, 7 years old

Seven-year-old working in a Carolina cotton mill, one of many youngsters exploited in industrial work.

Jewel and Harold Walker, Cotton Pickers

Six and five-year-old siblings who pick 20-25 pounds of cotton daily, their father promising them a wagon if they worked steadily.

Sadie Pfeifer, 48 inches high

A young spinner in a Carolina cotton mill, demonstrating the physical demands placed on child workers.

Cora Lee Griffin, Spinner

Adolescent girl working as a spinner in a Carolina cotton mill, part of Hine's extensive documentation of child labor.

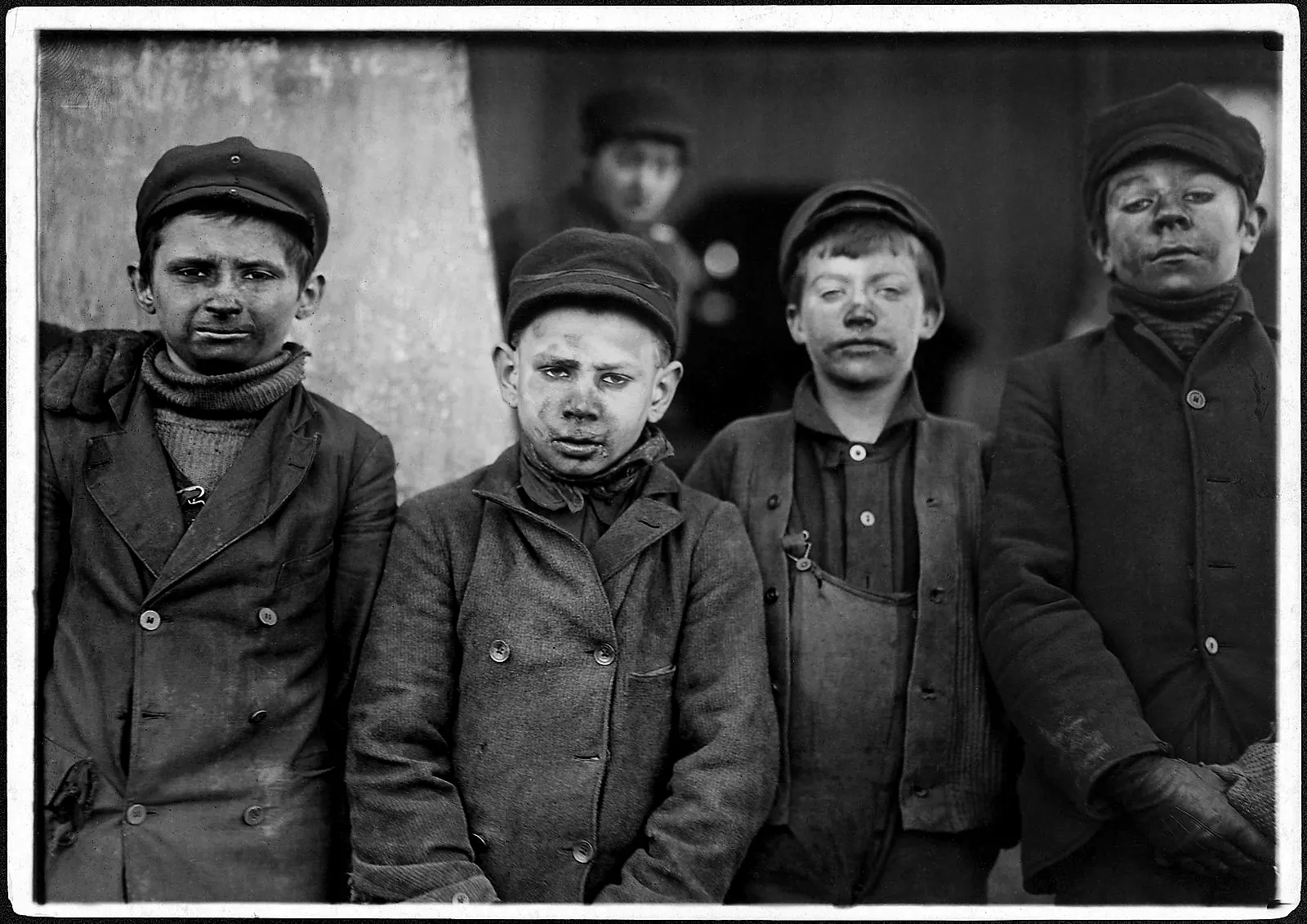

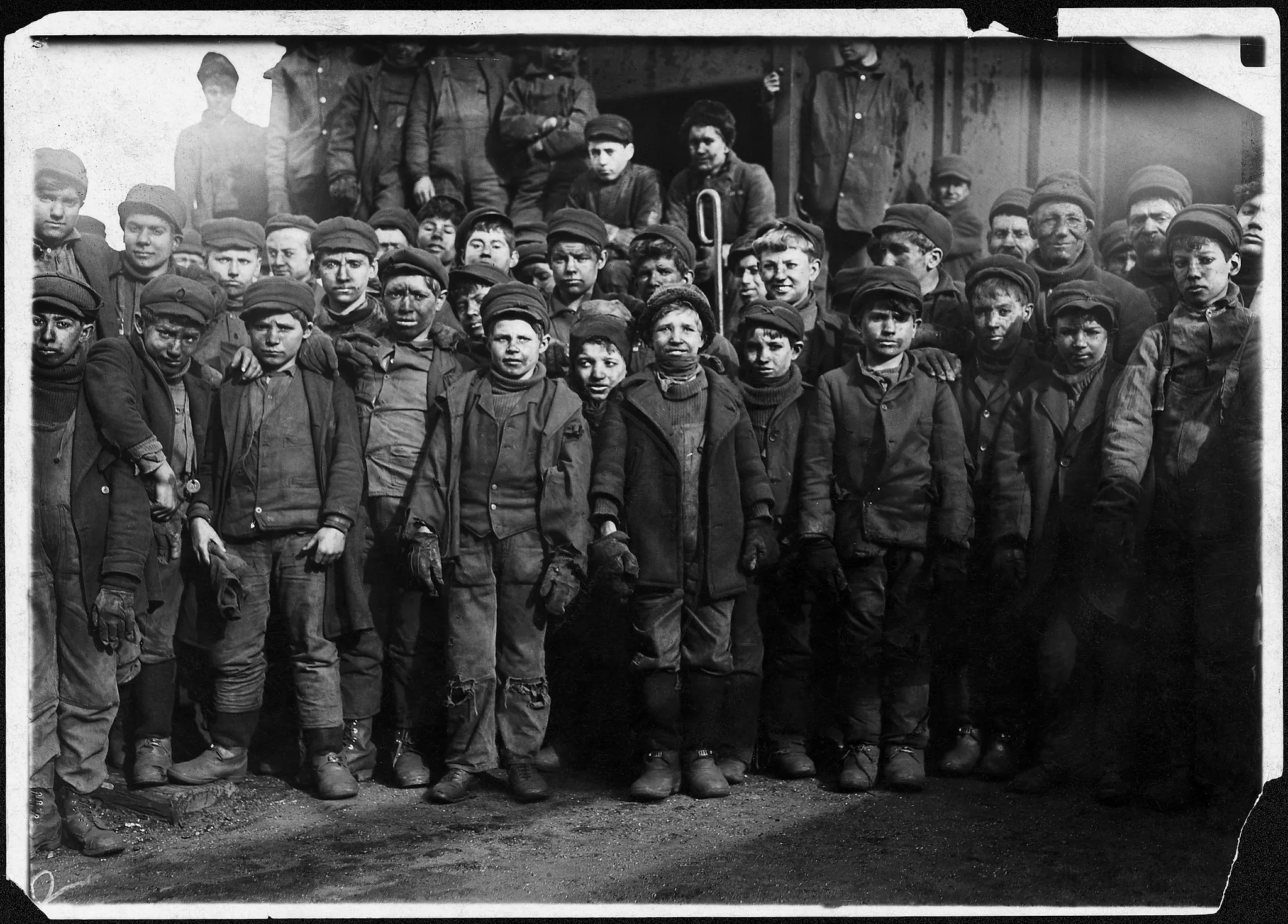

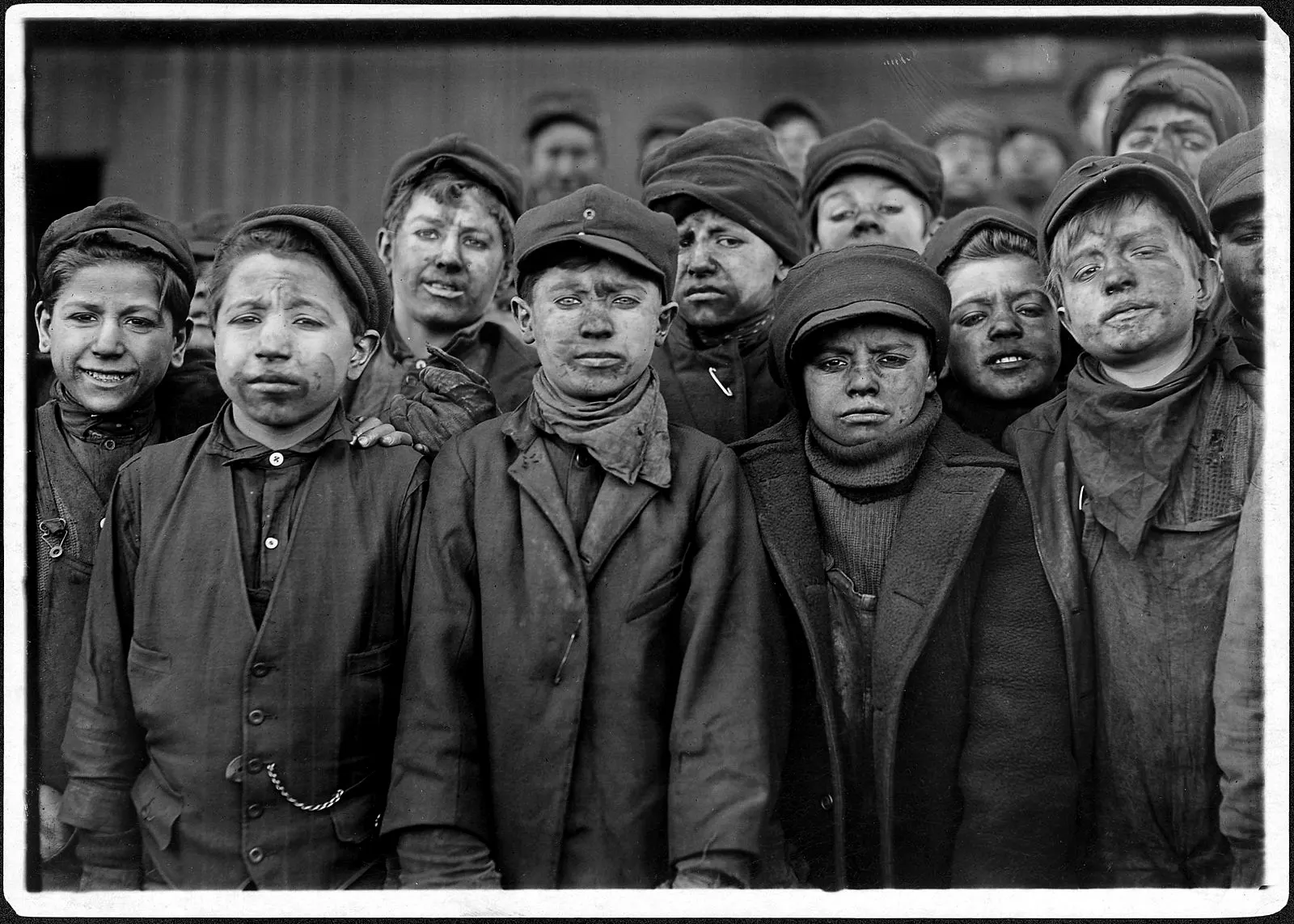

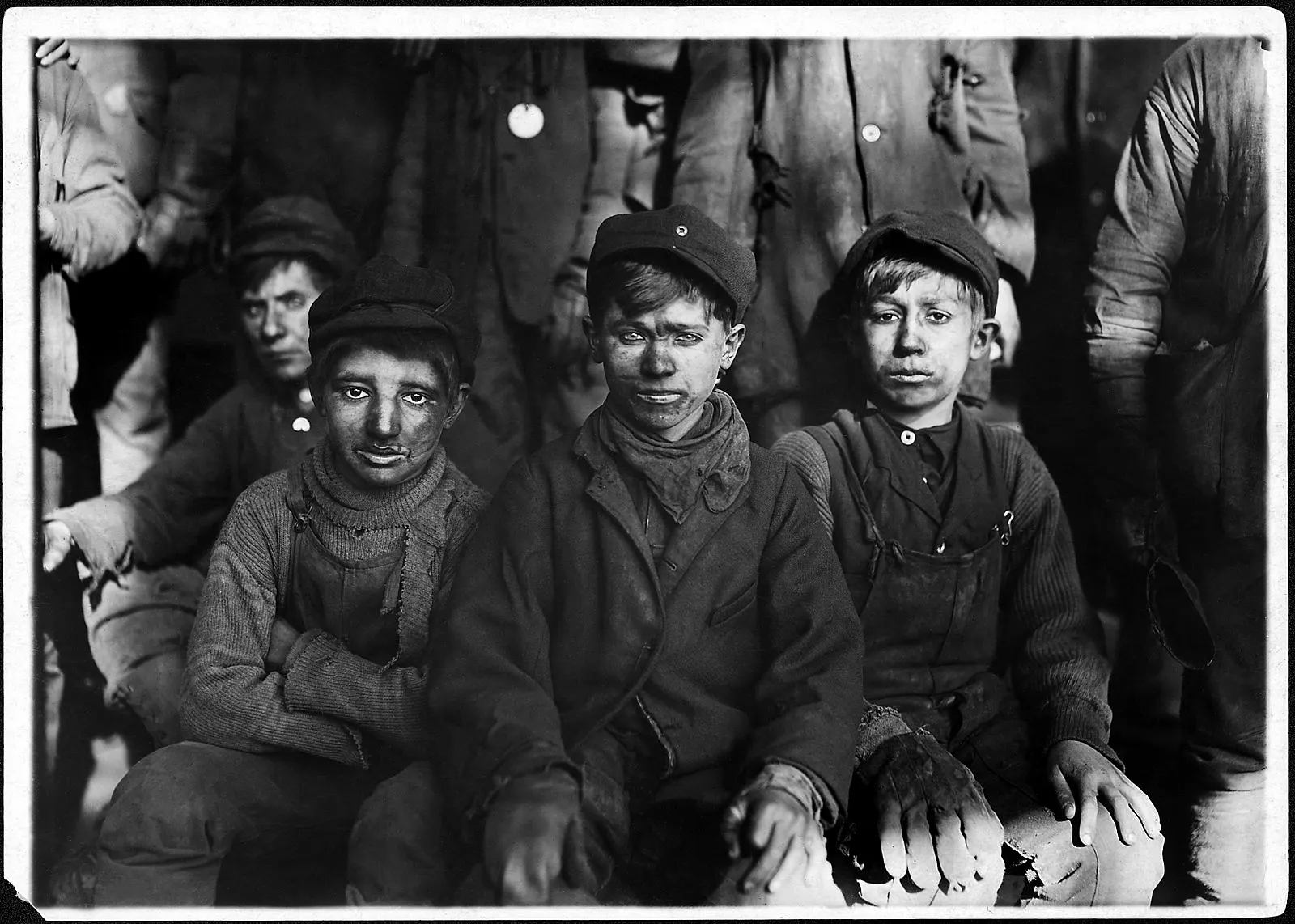

Breaker Boys, #9 Breaker, Hughestown Borough

Young coal breaker boys pose grimly for Hine's camera, their faces covered in coal dust, representing the harsh reality of child labor in American mines.

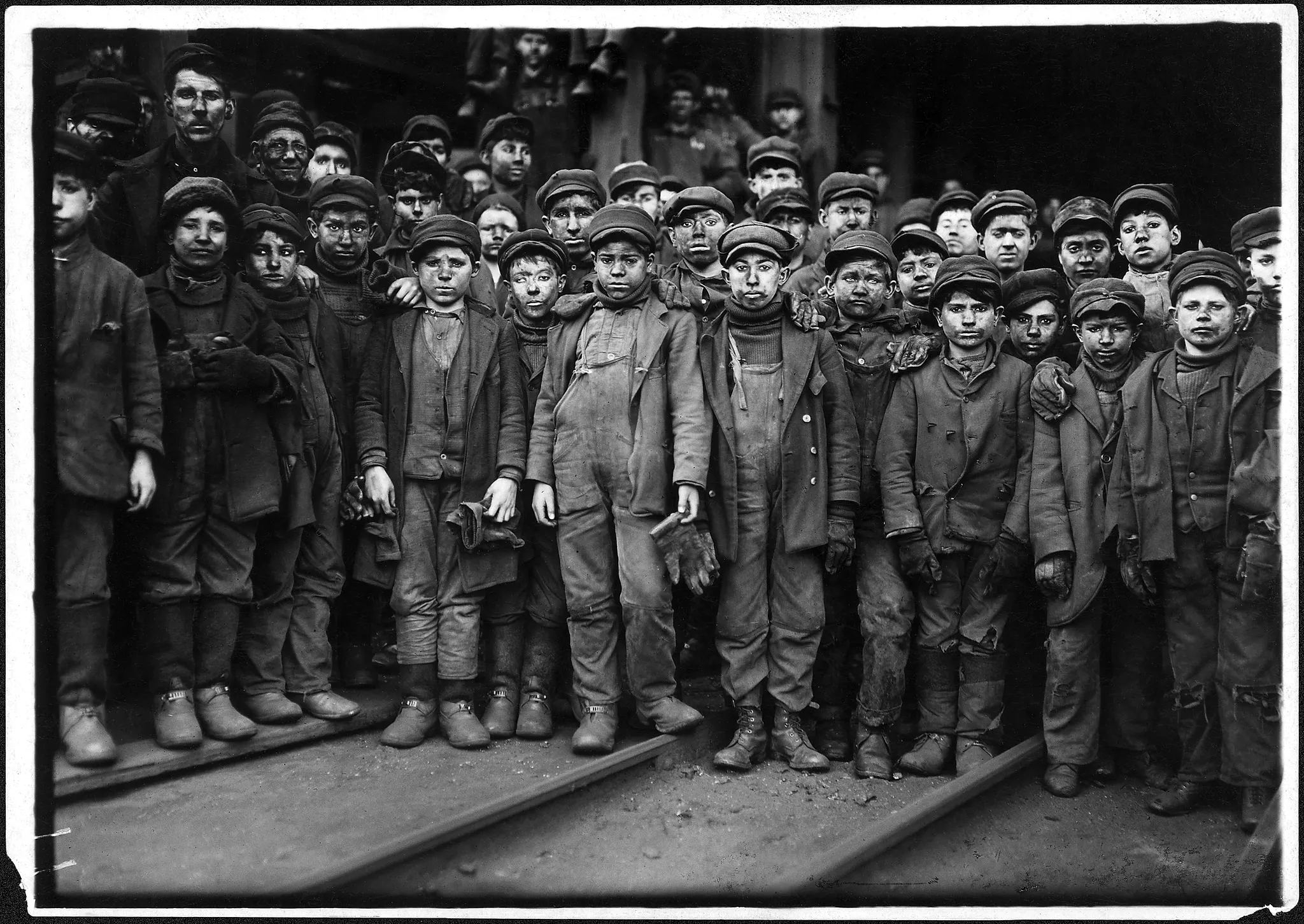

Group of Breaker Boys in #9 Breaker

Group portrait of breaker boys working in dangerous coal processing facilities.

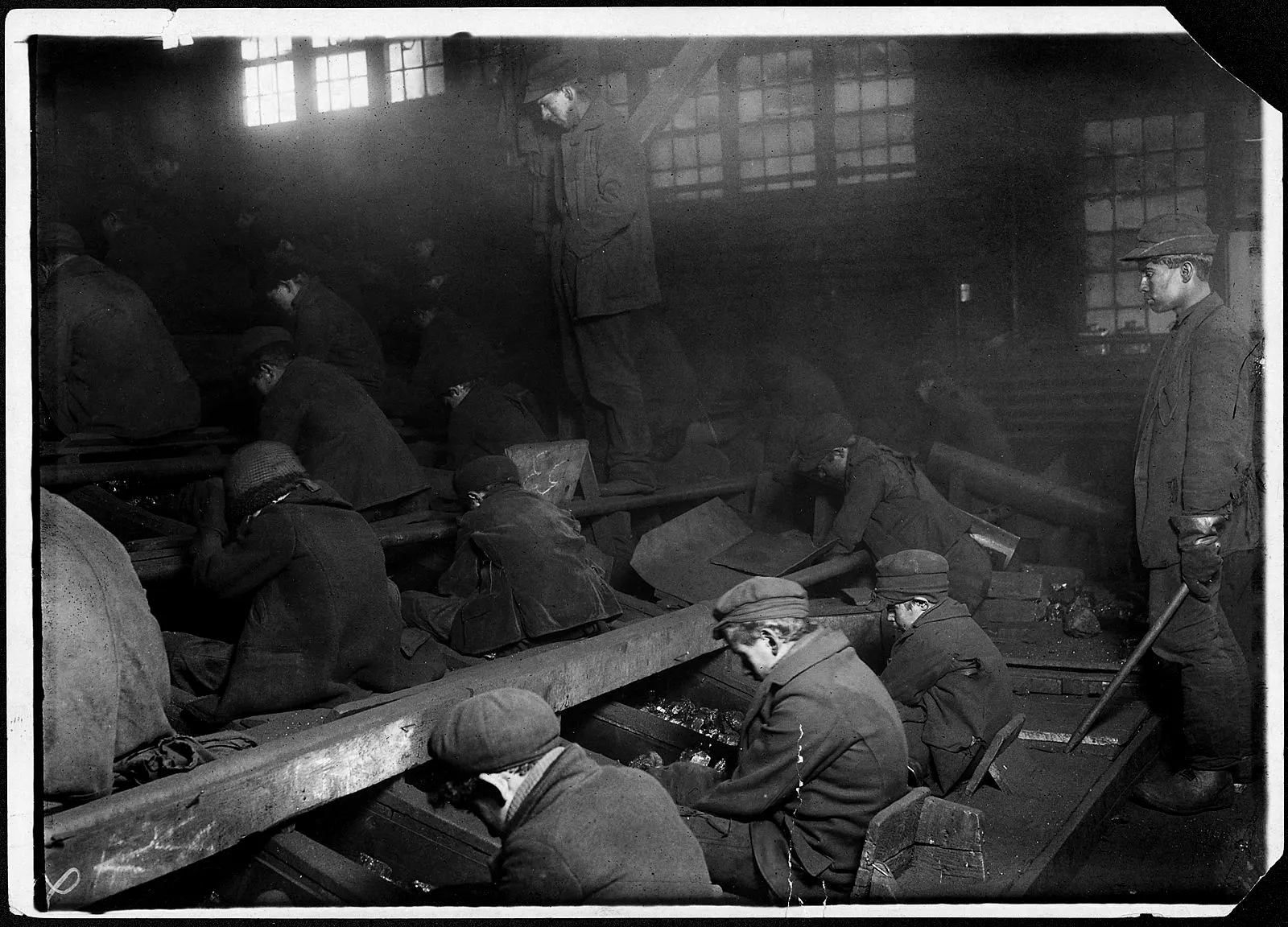

Breaker Boys Working in Ewen Breaker A

Child workers in the Ewen Breaker facility, showing the industrial environment where children labored.

Breaker Boys Working in Ewen Breaker B

Another view of child workers in the dangerous coal processing environment.

Noon Hour in the Ewen Breaker

Breaker boys during their brief lunch break, highlighting the long hours of child labor.

View of the Ewen Breaker

External view of the coal breaker facility where children worked in dangerous conditions.

Breaker Boys, Smallest is Angelo Ross

Group of breaker boys with the smallest worker identified as Angelo Ross, emphasizing the youth of these laborers.

Group of Breaker Boys, Smallest is Sam Belloma

Another group of child coal workers, with Sam Belloma identified as the youngest.

Breaker Boys, Woodward Coal Mines

Child workers at the Woodward Coal Mines, demonstrating the widespread nature of child labor in Pennsylvania coal industry.

Climbing into America

Immigrants ascending stairs at Ellis Island, symbolizing their journey into American life.

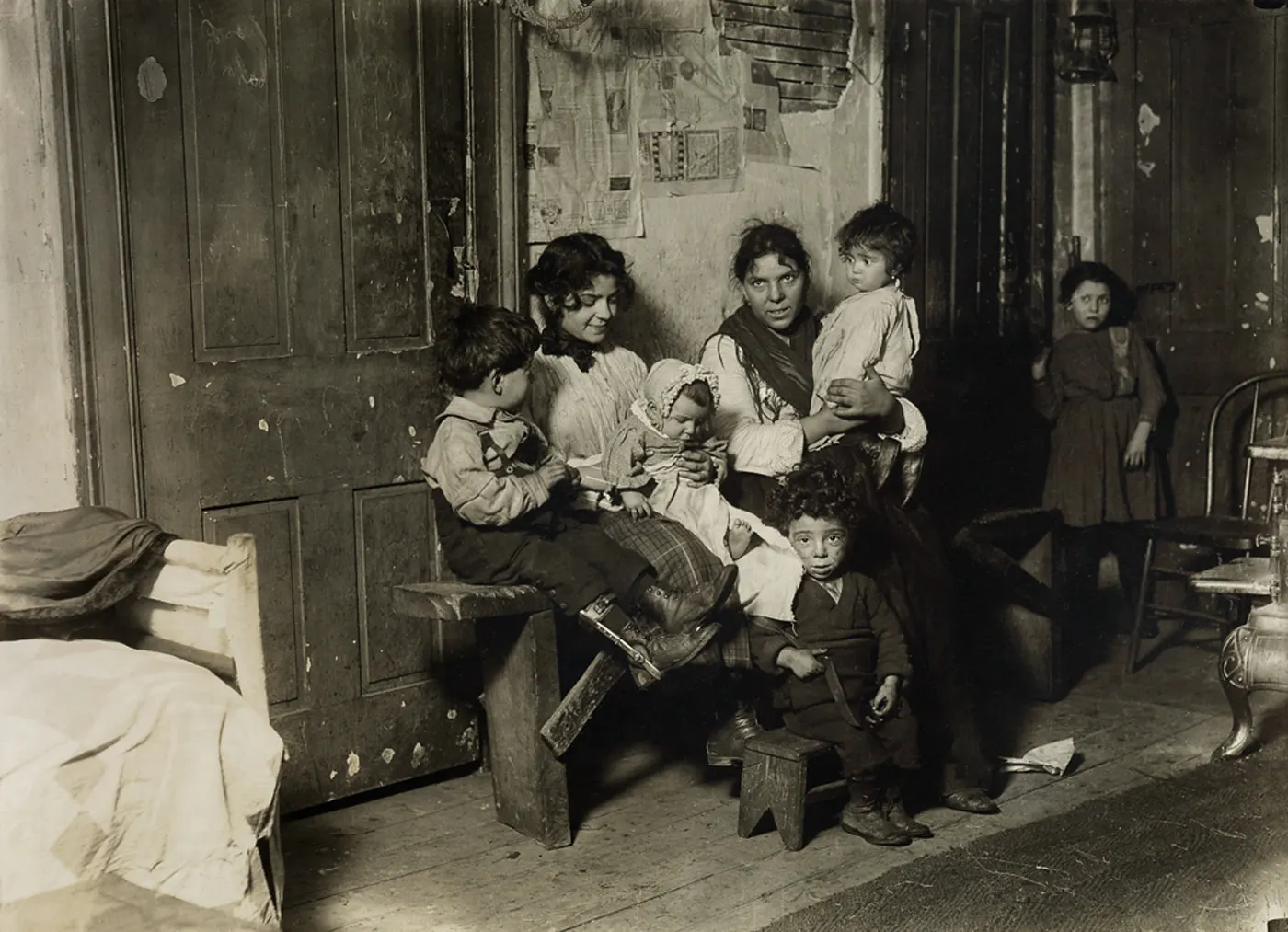

Italian Family in Baggage Room

An immigrant family navigating the complex processing system at Ellis Island, part of Hine's early documentation of American immigration.

Italian Family on Ferry Boat

Italian immigrants on the ferry approaching Ellis Island, capturing the hope and uncertainty of their journey.

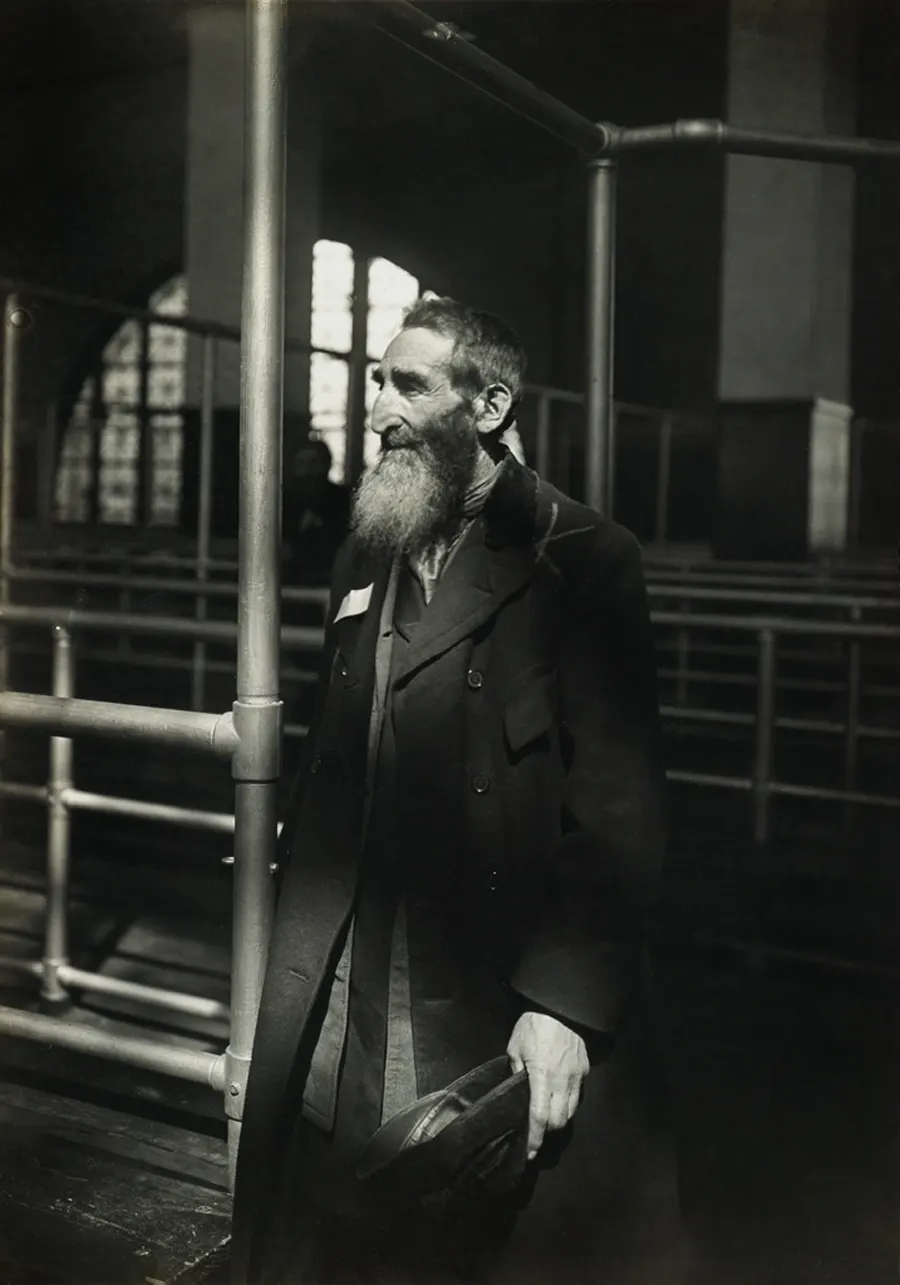

Patriarch at Ellis Island

Elderly immigrant man at Ellis Island, representing the family leaders who brought their clans to America.

Russian Family at Ellis Island

Russian immigrant family during processing at Ellis Island, showing the diversity of arrivals.

Slavic Immigrant at Ellis Island

Portrait of a Slavic immigrant, demonstrating Hine's ability to capture individual dignity within mass immigration.

Mother and Child, Ellis Island

Tender moment between mother and child during the immigration process, showing the human side of mass migration.

Newsies, New York

Young newspaper vendors on the streets of New York, highlighting urban child labor.

Noon Hour in East Side Factory District

Factory workers during lunch break in New York's East Side, documenting industrial working conditions.

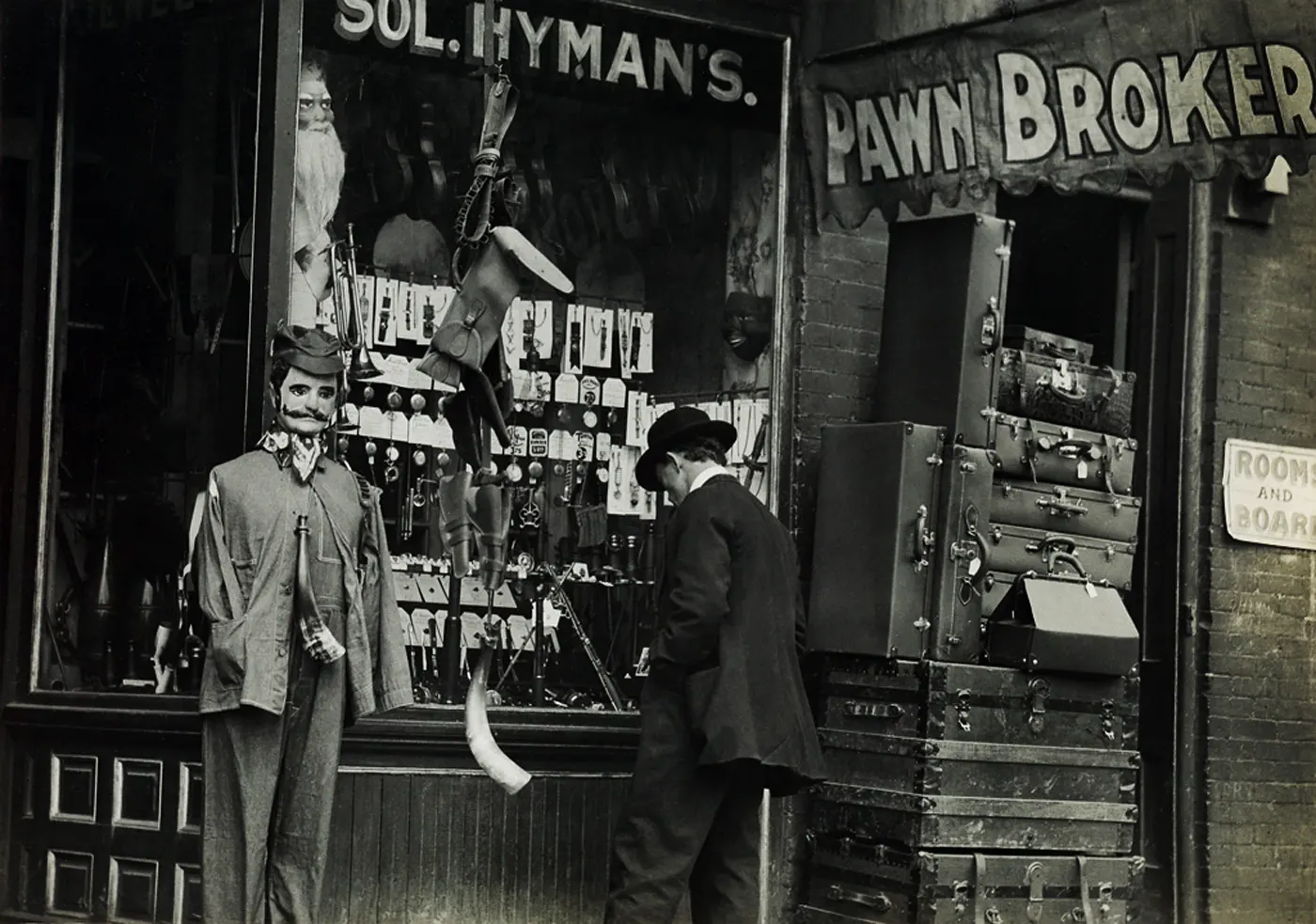

Nashville

Street scene in Nashville, part of Hine's broader documentation of American social conditions.

Tenement Family, Chicago

Family in Chicago tenement housing, documenting urban poverty and living conditions.

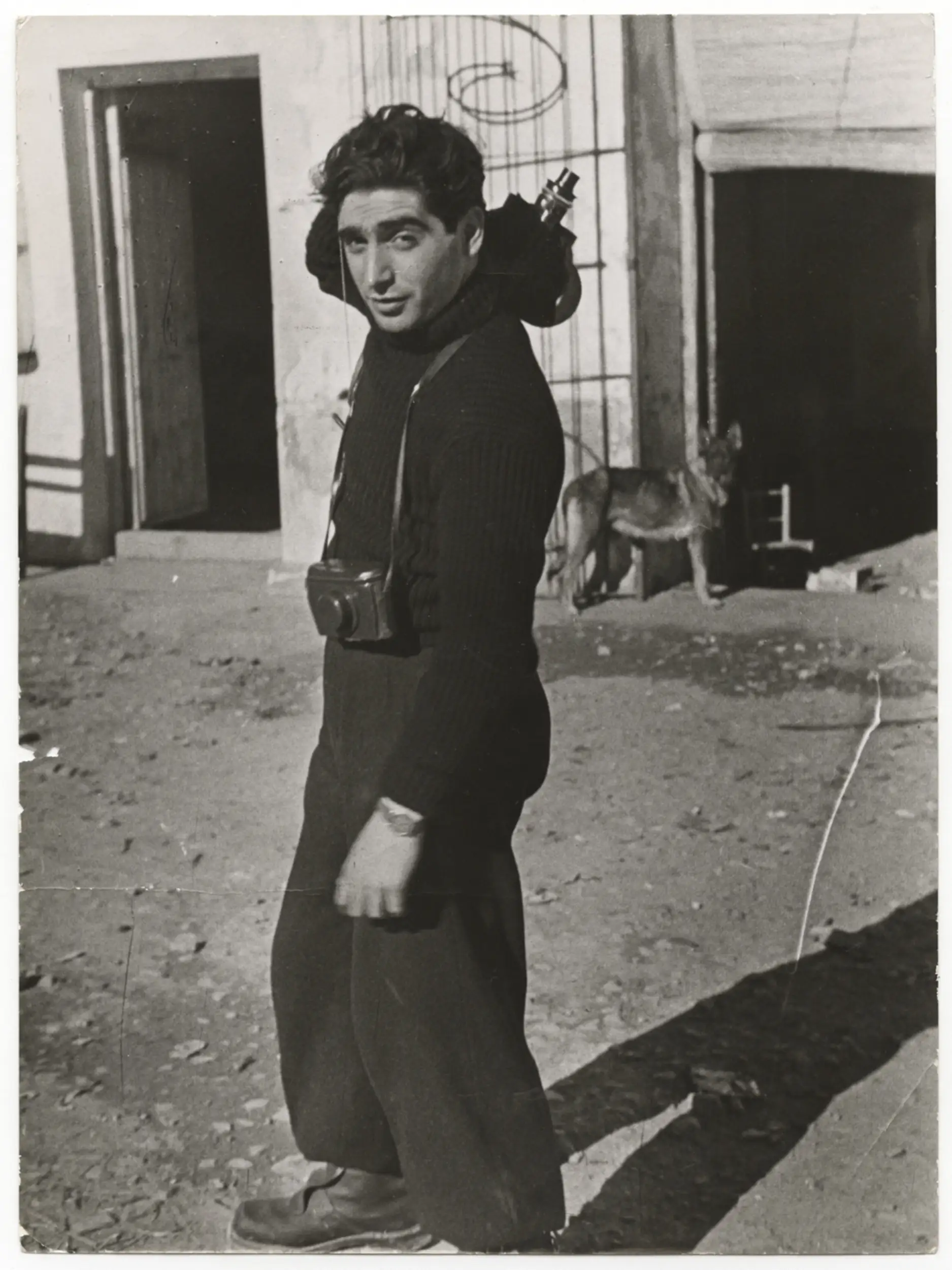

The Sociologist with a Camera

Lewis Wickes Hine (1874-1940) transformed documentary photography into a powerful instrument of social reform. Born in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, and trained as a sociologist, Hine pioneered the use of photography as evidence for social change, creating images that would fundamentally alter American labor laws and reshape public consciousness about child welfare.

His famous declaration, “There were two things I wanted to do. I wanted to show the things that had to be corrected. I wanted to show the things that had to be appreciated,” encapsulated a career dedicated to revealing both society’s injustices and humanity’s dignity.

Early Life and Educational Foundation

Following his father’s death in an industrial accident, Hine worked to support his family while pursuing his education. He studied sociology at the University of Chicago, Columbia University, and New York University, earning a profound understanding of social dynamics that would inform his photographic approach.

In 1901, Hine became a teacher at the Ethical Culture School in New York City, where he introduced photography as an educational tool. This progressive institution encouraged students to engage with social issues, setting the stage for Hine’s revolutionary work.

Three Defining Phases of Documentary Innovation

Hine’s photographic career can be understood through three transformative phases that revolutionized documentary photography. His Ellis Island period (1904-1909) established photography’s power to humanize social issues, documenting immigrants with unprecedented dignity and empathy. The National Child Labor Committee years (1908-1918) transformed him into America’s most influential social reform photographer, using his camera as a weapon against child exploitation. Finally, his Empire State Building project (1930-1931) demonstrated photography’s ability to celebrate human achievement and technological progress, marking his evolution from social critic to chronicler of American triumph.

Each phase built upon the previous, creating a comprehensive body of work that spans from exposing society’s darkest injustices to celebrating its greatest achievements.

Ellis Island: First Encounters with Documentary Photography

Between 1904 and 1909, Hine took his students to Ellis Island to photograph the thousands of immigrants arriving daily. This project marked his recognition of photography’s power to create empathy and understanding. He captured over 200 photographs of immigrants, creating dignified portraits that challenged prevailing stereotypes.

“I wanted to show the things that had to be appreciated.”

These early works demonstrated his ability to see subjects as individuals rather than statistics, establishing a compassionate approach that would define his career.

The Russell Sage Foundation and Pittsburgh Survey

In 1907, Hine joined the Russell Sage Foundation as staff photographer for the landmark Pittsburgh Survey. This comprehensive sociological study examined industrial working conditions in America’s steel capital. His photographs documented the harsh realities of industrial labor, combining artistic composition with rigorous social documentation.

The Pittsburgh Survey established Hine’s reputation as America’s preeminent social documentary photographer, proving that photography could serve both aesthetic and investigative purposes.

The National Child Labor Committee Years

Hine’s most consequential work began in 1908 when he joined the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) as chief photographer. For nearly a decade, he traveled across the United States, documenting the widespread exploitation of children in mines, mills, factories, and fields.

Investigative Methods and Dangerous Work

Hine’s work required extraordinary courage and ingenuity. Factory owners and foremen frequently threatened him with violence, understanding that his photographs could expose their illegal practices. He developed sophisticated methods to gain access to restricted areas:

- Disguising his identity: Posing as a fire inspector, Bible salesman, postcard vendor, or industrial photographer

- Measuring children covertly: Using the buttons on his vest to gauge heights

- Recording testimony secretly: Taking notes inside his coat pocket

- Documenting evidence: Photographing birth entries in family Bibles

Iconic Child Labor Photographs

Hine’s photographs became visual evidence of America’s exploitation of children. His most powerful images include:

Breaker Boys Inside the Coal Breaker - Young boys, some as young as eight, working in dangerous coal processing facilities, their faces blackened with coal dust, staring grimly into the camera with the resignation of adults.

Little Spinner in Carolina Cotton Mill - Child workers operating dangerous machinery, demonstrating the physical impossibility of such work for developing bodies.

A Nine-Year-Old Newsgirl in Hartford - Street children working long hours in all weather conditions, highlighting urban child labor beyond factory walls.

Artistic Innovation and Social Documentation

Hine’s genius lay in combining rigorous social documentation with artistic sophistication. He understood that emotionally powerful images would be more effective than mere evidence. His photographs displayed:

- Compositional mastery: Perfect balance and framing that elevated subjects

- Dignified portraiture: Photographing children at their eye level, never looking down

- Contextual storytelling: Including environmental details that revealed working conditions

- Human connection: Establishing dialogue with subjects that created authentic expressions

International Recognition and The Family of Man

Despite working primarily as a social reformer, Hine achieved significant artistic recognition. His work was featured in exhibitions at major institutions, and Edward Steichen included his photographs in the landmark The Family of Man exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1955.

World War I and Red Cross Work

During World War I, Hine served as a photographer for the American Red Cross, documenting relief efforts in Europe. After the Armistice, he remained in the Balkans, producing the photo story “The Children’s Burden in the Balkans” (1919). This work demonstrated his ability to apply his child advocacy perspective to international humanitarian crises.

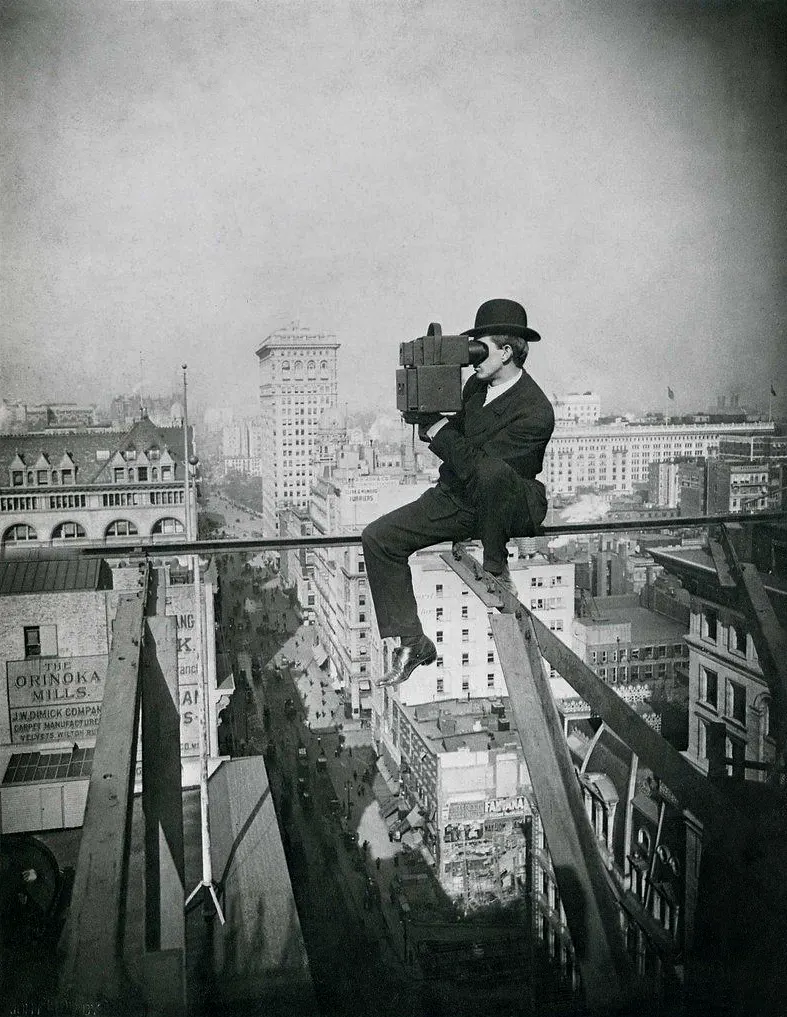

The Empire State Building Project

After returning from Europe, Hine was commissioned to document the construction of the Empire State Building in 1930-1931. These photographs marked a dramatic shift in his work, celebrating human achievement and technological progress rather than exposing social problems.

To capture the proper angles of the world’s tallest building, Hine had himself suspended in baskets and buckets over Manhattan’s streets, taking the same risks as the workers he photographed. His famous image “Icarus atop the Empire State Building” (1931) became an icon of American industrial achievement.

These photographs were published in 1932 as Men at Work: Photographic Studies of Modern Men and Machines, celebrating the individual worker’s interaction with modern technology.

Revolutionary Impact on Child Labor Laws

Hine’s photographs provided crucial evidence for the NCLC’s lobbying efforts. His images appeared in exhibitions, publications, and legislative hearings, creating unprecedented public awareness of child labor abuses. His work directly contributed to:

- The establishment of the Children’s Bureau in 1912

- State-level child labor legislation across the country

- The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which finally ended child labor in the United States

Later Years and Professional Struggles

Despite his monumental contributions to American society, Hine’s later years were marked by financial hardship. The Great Depression reduced demand for his services, and Roy Stryker of the Farm Security Administration considered him “difficult and past his prime,” refusing to hire him.

In 1936, Hine was appointed head photographer for the Works Progress Administration’s National Research Project, but this work was never completed due to funding cuts. By the late 1930s, he was nearly destitute, losing his house and applying for welfare.

Hine died on November 3, 1940, at age 66, in Dobbs Ferry, New York, as poor as any subject who had ever sat for his lens.

Artistic Legacy and Recognition

Despite the Museum of Modern Art initially declining to acquire his work after his death, Hine’s photographs eventually gained recognition as masterpieces of both documentary photography and social justice advocacy. The George Eastman House preserved his archive, ensuring future generations could study his revolutionary approach.

In 1939, Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland mounted a traveling retrospective exhibition that revived interest in his work, establishing his position in photography history.

Technical Innovation and Aesthetic Philosophy

Hine’s photographs emerged from the American Romantic movement, incorporating elements of transcendentalism and literary realism. Like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman, he believed in the inherent goodness of individuals corrupted by industrial society.

His aesthetic approach was characterized by:

- Objective realism: Representing subjects truthfully without artistic conventions

- Transcendental humanism: Seeing the soul within social circumstances

- Modernist composition: Creating perfectly balanced images that were revolutionary for their time

Alexander Nemerov observed in “Soulmaker: The Times of Lewis Hine” that Hine’s photographs function as “a kind of capsule containing the full flow of all we will ever be, and have been.”

The First True Social Documentary Photographer

While Alfred Stieglitz was still creating Pictorialist photographs like “The Terminal” (1892) in 1911, Hine was producing stark, modernist images that combined formal innovation with social purpose. His work predated and influenced the entire tradition of social documentary photography, from the Farm Security Administration photographers to contemporary photojournalists.

Climbing Into Immortality

What Alexander Nemerov called Hine’s “gradual climb into immortality” began with his photographs’ immediate impact on American law and society. Today, his images remain as relevant as when they were taken, serving as both historical documents and artistic achievements.

His photographs transcend their original purpose, becoming profound meditations on human dignity, social justice, and the power of visual testimony. They remind us that photography’s greatest achievement may be its ability to make visible the invisible, to give voice to the voiceless, and to transform individual suffering into collective action.

In Hine’s revolutionary approach to photography as social advocacy, we see the foundation of all subsequent documentary photography committed to social change. His legacy lives not only in museums and archives but in every photographer who believes their camera can help create a more just world.

[References: Art Blart, Howard Greenberg Gallery]